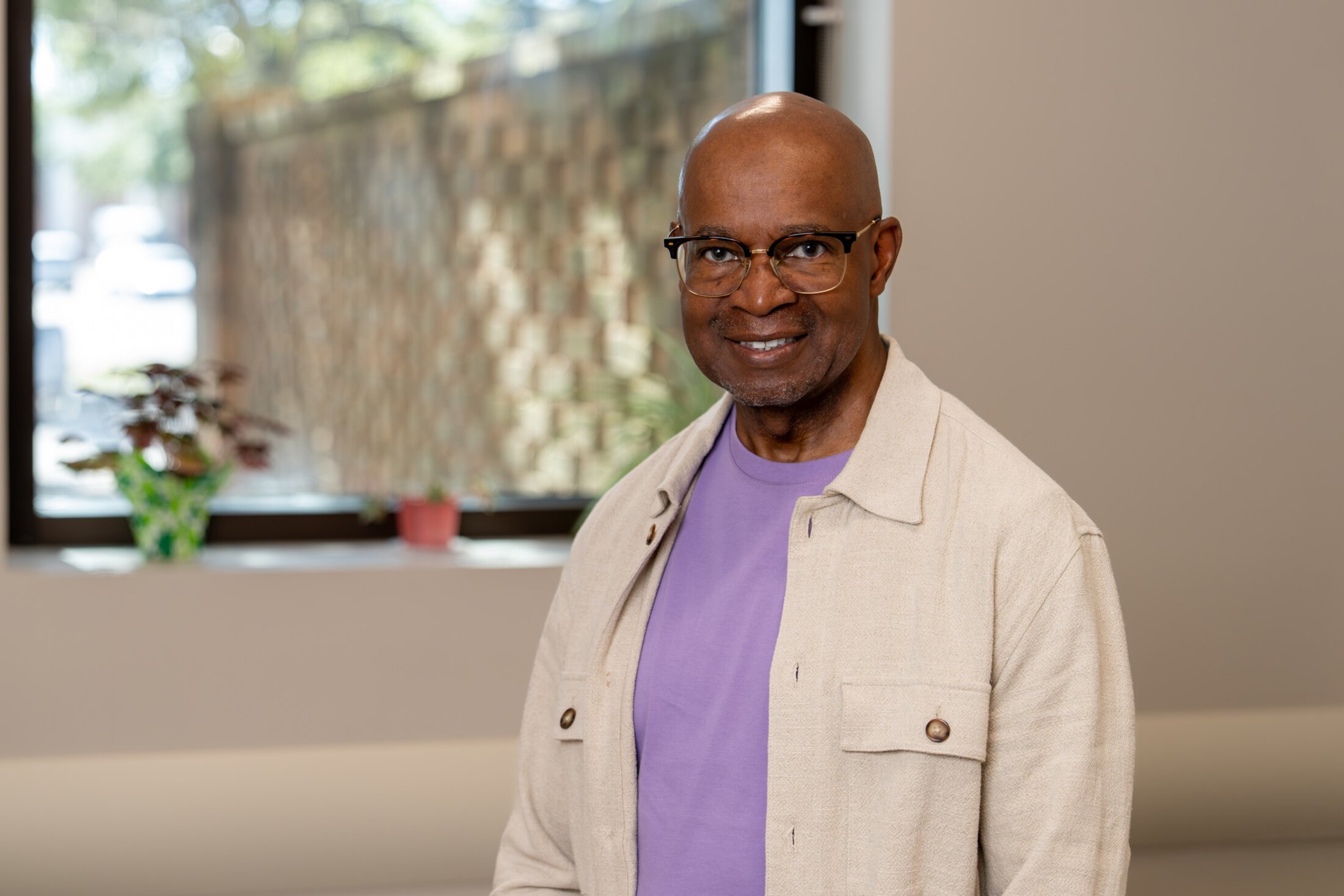

When Kenneth Reid was diagnosed with colon cancer at age 43, his doctors suggested genetic testing. But the Charleston native, who was living in Minnesota at the time, didn’t trust the idea.

“I had some reservations about what that would do to my future career, my family's future careers – I had two daughters – and whether that would be public record and they might be penalized in some way,” he said.

As a Black male, even though he worked in the health care system, there was an extra layer of concern about whether his information would be used against him, given past abuses in medical research.

But with time and experience – and a new diagnosis of prostate cancer – Reid not only changed his mind about genetic testing but became an advocate for it.

As a member of the Cancer Support Ministry at Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church in North Charleston, he has organized prostate cancer awareness breakfasts that include sharing information about the power of genetic testing.

Understanding his specific inherited genetic mutation has helped him, first, to realize that there was nothing he could have done differently to avoid having colon cancer at a young age and, second, to make choices about how to deal with his prostate cancer.

“It let me know how aggressive I needed to be about the treatment path that I chose,” he said. “That was invaluable information that actually gave me a sense of how to approach my treatment and to make decisions about my treatment. Life goes on, and you don't know what's going to happen. But right now, I'm living my best life because of the aggressive decisions I made based on the genetic findings.”

A family history of cancer

Reid knew that he had a strong family history of cancer. An aunt died of colon cancer before he was born. His mother also developed colon cancer and died from complications of the disease at age 63. So it was not entirely surprising when he was diagnosed.“I was diagnosed at 43, and I got 80% of my colon removed,” he said. “Fortunately for me, I resumed a normal life. So I was lucky. I thank God they caught it relatively early. I had some chemo follow-up, but after that, I resumed normal life.”

Reid and his wife were preparing to retire back to South Carolina when he was diagnosed, at age 65, with prostate cancer.

I'm living my best life because of the aggressive decisions I made based on the genetic findings.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men. It is often slow-growing and can sometimes be managed through active surveillance, which means that doctors regularly check on the cancer but wait to perform more intense treatments, like surgery or radiation, until the cancer becomes a threat.

In Reid’s case, however, the cancer quickly spread to a vertebra in his upper back. He underwent radiation, then completed his retirement move to South Carolina.

“Three or four months later, there was more activity, and the lesion appeared again on the T3 vertebra,” he said. “This time I had surgery. But in the process, they're still talking to me about genetic testing. So eventually I spit into a vial, and the rest, as they say, is history. So now I know I have a mutation in my MSH2 gene.”

The MSH2 gene normally helps to fix mistakes that occur when DNA is copied. Reid’s mutation in this gene means that he has a form of Lynch syndrome.

People with Lynch syndrome are at increased risk for colon, bladder and stomach cancer. Women have an increased risk of uterine and ovarian cancer, and men have an increased risk of prostate cancer. When someone has a Lynch syndrome mutation, there is a 50/50 chance that the mutation will be passed along to each child.

The evolution of genetic testing and the role of genetic counseling

A lot has changed in our understanding of genetics since Reid was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1998. The law has changed, too. The Genetic Information Discrimination Act, passed in 2008, forbids employers and health insurers from discrimination based on genetic information, which was one of Reid’s concerns when he was first diagnosed.

Researchers have also identified additional genetic mutations responsible for cancer.

“Genetic testing has really expanded within the past five to 10 years to where we're seeing a really wide range of cancer types,” said Clare McTighe, a certified genetic counselor at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center.

She met with Reid in 2023 after he was referred by his medical team.

“Prostate cancer itself is very common. But metastatic prostate cancer is not as common, and we know it is a little more likely to be hereditary,” she said. “So that's why he was referred. And then when I was prepping his chart and collecting his personal history, I learned he also had a history of colon cancer at 43 years old. So he had two examples of what we'd call red flags.”

McTighe emphasized that genetic testing is voluntary.

“We like to say that genetic counseling does not equal genetic testing. We do have patients who will come talk to us for an hour about the genetic testing, and then they decide either they don't want to do it or they want to take some time to think about it,” she said.

In Reid’s case, he decided to go forward with the testing. When patients have a positive result for a cancer-causing genetic mutation, their counselors talk them through what it means – both for the patient and for family members.

“A big piece of what we do is discussing the importance of the result for family members,” McTighe said. “A resource we use in genetics is family letters. We provide the patient with a generic letter that briefly describes their results, why it's important for family members to get tested and how they can get tested. And I think patients find that helpful because it can be a lot to, first, hear this information yourself. But then to go and try to relay that to your family can be very difficult. And so that family letter serves as something that they can give to their family members.”

Since genetics is a newer field, it's very rapidly evolving. We learn new information every day.

Patients with genetic mutations are referred to the Hollings Hereditary Cancer Clinic, which ensures that people with cancer-causing mutations have a dedicated team helping them to get more frequent or supplemental screenings, depending on the cancer type, than are recommended for the general public.

“That's why the hereditary cancer clinic was established – so there's a hub where there's someone who's trained in genetics keeping up with the patient surveillance and checking in with them on a regular basis to make sure that they're up to date,” McTighe said. “Since genetics is a newer field, it's very rapidly evolving. We learn new information every day. The guidelines and recommendations for people who test positive do get updated pretty regularly, and the clinic is there to keep patients and their primary providers informed of those updates.”

Managing risk to enjoy life

Reid said that getting the genetic testing done empowered him to make decisions that he can feel comfortable with. Now, he’s enjoying retirement – playing pickleball, running after his grandkids and feeling like he’s finally back home after so many years away.He's also committed to giving back.

“I feel like I'm benefiting from advances in medicine, and I feel that I have an obligation to leave this life better than I found it. So maybe this is my purpose, you know? And that's why I did the cancer awareness event at my church,” he said.

“I'm a man of faith. I respect my doctors. I know that they have the scientific and medical expertise, but ultimately, God is in control.”

Recent Hereditary Cancer stories