Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is one of the most aggressive and treatment-resistant forms of breast cancer. It grows quickly, spreads early and lacks the hormone receptors that make other breast cancers treatable with targeted therapies. Even when patients initially respond to treatment, the cancer often returns and is more resistant than before.

A new study in Breast Cancer Research points to a promising strategy to overcome the cancer’s resistance. Researchers at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center developed an antibody that blocks several of the ways TNBC cells survive, grow and evade the immune system. In early testing, the antibody suppressed primary tumor growth and the spread of cancer to the lungs and reenergized cancer-fighting immune cells. It even killed cancer cells that had stopped responding to chemotherapy.

A new target in an immune-resistant cancer

This preclinical study focused on a protein called secreted frizzled-related protein 2 (SFRP2), which acts as a cancer enabler – fueling tumor growth by supporting new blood vessels, blocking cell death and weakening immune cells that should attack the cancer.

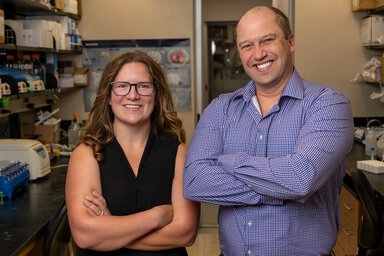

The work builds on nearly two decades of research on SFRP2 by Nancy Klauber-DeMore, M.D., a breast surgical oncologist who co-leads Hollings’ Developmental Cancer Therapeutics Research Program. It brought together a broad multidisciplinary team across MUSC’s Surgery, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine departments.

“My lab first identified the role of SFRP2 in breast cancer in 2008,” Klauber-DeMore said. “Since then, we’ve discovered its mechanism of action in breast cancer growth, metastasis and immune exhaustion and developed an antibody to block SFRP2.”

In this study, the researchers, also led by MUSC surgical resident Lillian Hsu, M.D., and former resident Julie Siegel, M.D., tested the effects of a humanized monoclonal antibody – a highly targeted molecule designed to attach to SFRP2 and inhibit its cancer-causing effects.

Reprogramming the cancer’s immune environment

To confirm that SFRP2 could be a useful target for TNBC and investigate the antibody’s role in treating it, the researchers first examined human triple-negative breast tumors. They found that SFRP2 was present not only in the tumor cells themselves but also in nearby immune cells, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes as well as macrophages.

“This is the first time anyone has demonstrated that SFRP2 is expressed on tumor-associated macrophages,” Klauber-DeMore said. “That finding alone opens up an entirely new way of understanding and potentially manipulating the immune microenvironment.”

Macrophages can be broadly categorized into two types: M1 macrophages that activate the immune system to fight cancer and M2 macrophages that suppress immunity to help cancer grow. In TNBC, macrophages usually skew toward the M2 type. But when treated with the SFRP2 antibody, the macrophages released a surge of interferon-gamma, a key immune signal that pushed them toward the tumor-fighting M1 state. In mice whose cancer had already spread, the antibody still induced this favorable M1:M2 ratio, indicating that it could “retrain” the immune system to fight cancer even in advanced disease.

“We discovered that it pushes macrophages toward the ‘good’ M1 state – without the toxic effects you’d see if you gave interferon-gamma directly,” Hsu said. “TNBC is so hard to treat, and so many therapies come with serious toxicities, so finding a way to activate the immune system without adding new side effects is especially meaningful.”

The antibody also re-energized cancer-fighting T-cells, which often become exhausted and stop working effectively in TNBC. Once treated with the antibody, nearby T-cells became more active, suggesting that the treatment may strengthen immune responses that are often weakened in cancer and reduce the success of immunotherapy.

A highly targeted approach against cancer

In two models of advanced TNBC, mice treated with the antibody developed far fewer lung tumors than those not treated with the antibody. Lung metastases signal that cancer has spread through the bloodstream and can make outcomes far worse for patients.

Not only was the antibody effective – it was highly targeted. When the researchers tracked its movement in the body, they found that it concentrated in tumor tissue but not in healthy organs or normally growing cells. That precision contrasts with traditional chemotherapies, which kill cells more broadly and contribute to the problematic side effects that many patients experience during treatment.

Finally, the team tested whether the antibody could tackle one of the biggest hurdles in cancer treatment: resistance to chemotherapy. Doxorubicin, a standard drug used for TNBC, often works at first, but many tumors eventually stop responding. After creating cancer cells that no longer responded to doxorubicin, the researchers found that the antibody still triggered strong cell death in these hard-to-treat cells.

“That’s a very encouraging finding,” Klauber-DeMore said, “because it suggests the therapy may be effective even when standard treatments fail.”

A new therapeutic direction for treating cancer

This study revealed that SFRP2 is present at high levels in the tumor ecosystem: in both cancer cells and surrounding immune cells, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and tumor-associated macrophages. That suggests the SFRP2 antibody could act on multiple fronts at once by weakening the tumor, strengthening the immune response and bypassing treatment resistance.

Equally important, SFRP2 did not accumulate in healthy blood or immune cells, unlike many other immune-related treatments. That opens the door to adapting the antibody as a potent cancer therapy that treats the disease while minimizing unwanted side effects.

By showing that SFRP2 sits at the crossroads of tumor growth, immune suppression and treatment resistance, this study lays the foundation for a new kind of precision therapy that could work alongside or enhance existing immunotherapies for TNBC.

“Our hope,” Klauber-DeMore said, “is that this will one day offer patients a new option – one that not only treats the cancer but also re-engineers the immune system’s ability to fight it.”

While further research is needed, these early findings offer promise. The antibody has been licensed to Innova Therapeutics, a Charleston-based biotechnology company co-founded by Klauber-DeMore, which is working to raise funds for a first-in-human clinical trial. The therapy has also received Rare Pediatric Disease and Orphan Disease designations from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for osteosarcoma, another cancer where SFRP2 plays a major role. The FDA designations do not mean the antibody can be used in patients yet, but they provide incentives to support the drug’s development as it moves toward clinical trials.

“The preliminary data are really encouraging,” Hsu said. “I feel grateful to have been part of research that could one day help so many patients.”

Lillian Hsu, Julie Siegel, Patrick Nasarre, Nathaniel Oberholtzer, Rupak Mukherjee, Eleanor Hilliard, Paramita Chakraborty, Rachel A. Burge, Elizabeth C. O’Quinn, Olivia Sweatt, Mohamed Faisal Kassir, G. Aaron Hobbs, Michael Ostrowski, Ann-Marie Broome, Shikhar Mehrotra and Nancy Klauber-DeMore. Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 2 Monoclonal Antibody-Mediated IFN-ϒ Reprograms Tumor-Associated Macrophages to Suppress Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Research. [5 December 2025]. doi: 10.1186/s13058-025-02176-6.

Funding from the South Carolina SmartState Program (W81XWH-18-1-0007), National Cancer Institute (P30CA138313), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM130457), Department of Defense Breakthrough Level II Award and Hollings Cancer Center Abney Fellowship supported this research.