Cervical cancer is highly preventable, yet thousands of people in the U.S. are diagnosed and die from the disease annually, often due to a lack of timely screening and treatment. Two major national bodies – the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration – recently updated their cervical cancer screening guidelines to include self-collection for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing as an approved screening option, a move that could significantly expand access nationwide.

The guidelines come as national screening rates continue to fall below public health targets, driven in part by persistent barriers to screening for many people. HPV self-collection directly addresses some of those challenges by allowing patients to collect their own samples for testing, either at home or in a clinical setting.

While the approach is not yet widely available, researchers say the new guidance signals growing momentum for self-collection as a tool to reach people who are overdue for screening and to strengthen cervical cancer prevention efforts more broadly.

What is HPV self-collection?

Many people are familiar with Pap smears to assess cervical cancer risk, but HPV tests are different.

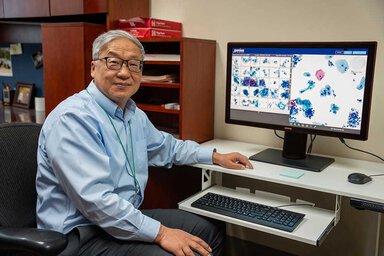

“A Pap smear looks for abnormal cell changes in the cervix,” said Trisha Amboree, Ph.D., a cervical cancer prevention researcher at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center. “An HPV test looks for the virus that causes most abnormal cervical cell changes that can lead to cancer. The tests tell us different things, and both are important.”

Self-collection can be incredibly helpful for reducing screening barriers. It’s not about replacing provider-performed tests but reaching those who aren’t getting screened.

Pap smears involve medical professionals collecting cervical cells and examining them under a microscope to look for abnormal changes that are already present. HPV tests detect high-risk strains of the virus that increase the chances of developing abnormal cell changes in the future.

Both screening tests can help to detect cancer earlier, when it is easier to treat. Timely screening is one of the most effective ways to detect precancerous changes and early-stage cancers, and women who have never been screened face higher risks of developing invasive cervical cancer.

Because HPV infections cause almost all cervical cancers, the updated federal guidelines endorse HPV testing, with samples collected by a patient or a clinician, as the primary screening method for average-risk adults. Importantly, research shows that patient-collected samples perform as well as clinician-collected samples for detecting high-risk HPV.

How does HPV self-collection work?

In self-collection, patients use a long, sterile swab, similar to a COVID-19 test swab, to gently collect a sample from the vaginal canal. This can be done either in a clinic or at home, depending on the device used. In clinical settings, patients collect the sample privately and return it to their clinicians. At home, patients receive a mailed kit, collect the sample and send it back to a designated laboratory.

In a study comparing the acceptability of self- versus clinician-performed screening tests, 59% of participants preferred self-collection, describing it as easy, convenient and more private. Nearly all said they would be willing to use self-collection again.

Once a sample is collected and analyzed, the next steps follow national screening and management guidelines. For instance, if the highest-risk HPV strains are detected, patients may be referred directly to a colposcopy for a closer examination of their cervix. For other strains, the next step may be a Pap smear to check for cervical cell changes or a repeat HPV test in one year.

Why does HPV self-collection matter?

HPV self-collection could play a powerful role in closing cancer screening gaps. But Amboree emphasized that it is not meant to replace clinician-performed tests for those who are already receiving routine screening.

“Self-collection can be incredibly helpful for reducing screening barriers,” she said. “It’s not about replacing provider-performed tests but reaching those who aren’t getting screened.”

Research supports this. In a recent randomized clinical trial involving Hollings researchers, women who were overdue for screening were almost three times more likely to get screened when offered self-collection compared with those asked to come in for a clinician-performed test.

One reason is that self-collection, particularly when used at home, can reduce barriers to screening, such as a lack of transportation, childcare or time off work. It can also help people who have discomfort with pelvic exams. Amboree noted that it may be especially impactful for rural communities, lower-resourced populations and people without consistent health care access.

“That speaks to what self-collection can do,” she said. “It can expand access by adding another tool to the toolkit.”

Why is HPV self-collection not widely available yet?

At MUSC and across the country, experts are evaluating how self-collection could fit into real-world clinical care.

To date, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three self-collection devices: two for clinic use and one for at-home testing. But putting them into practice is complex. Most health care systems remain in an early assessment phase, working through logistics, such as laboratory and IT workflows and follow-up and management strategies.

“This is all fairly recent,” Amboree said. “There are implementation and integration questions we’re trying to answer. National bodies are also developing resources to facilitate adoption.”

With screening declining in the U.S., we need to utilize every tool we have.

As health systems work through these logistics, researchers and clinicians are focused on introducing self-collection in a safe and accessible way. Amboree emphasized that thoughtful implementation will be key to ensuring the test reaches the people who stand to benefit most.

“With screening declining in the U.S., we need to utilize every tool we have,” she added. “And we want to make sure we do it right. Self-collection could eventually play a critical role in preventing a very preventable cancer.”

Recent Gynecologic Cancer stories