Taking Out the Trash

MUSC scientists have discovered, for the first time in people, a previously unknown pathway that helps the brain to drain away waste.

Hollings Cancer Center researchers hope to commercialize a blood test soon that could improve patients’ chances of surviving liver cancer. The mortality associated with liver cancer is predicted to continue to rise at an annual rate of almost 3% in men and 2% in women, making it the cancer with the greatest increase in mortality in the nation over the past 10 years.

Anand Mehta, D.Phil., a Hollings Cancer Center researcher at the Medical University of South Carolina, and colleagues received more than $6 million from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to look into the development of biomarkers for the disease, which could serve as a blueprint for investigating and understanding other cancers as well.

In 2019 alone, Mehta received four NCI grants that have furthered his efforts to target liver cancer, which is predicted to continue rising in the nation and to exceed 50,000 cases by 2023. The most recent grant seeks to detect hepatocellular carcinoma –the most common type of liver cancer – at an early stage, using an accessible, affordable test.

Mehta said the big problem with liver cancer is how hard it is to detect it early since many people are unaware they have it until it has progressed to an advanced stage. “If there’s a tumor on your liver, the only thing they can do right now is cut it out. They don't just cut out the tumor, they'll cut out entirely around it. If that's half your liver, you're not going to survive. There's nothing they can do for you.”

On the other hand, if the tumor is small, it can be surgically removed, and the liver will recover. “We've known for years that if you catch liver cancer early, your overall survival is greater than 60 months, so it's a cure, almost. But if it’s caught late, your overall survival rate is less than 20 months, and you'll succumb pretty quickly. So early detection is essential for liver cancer.”

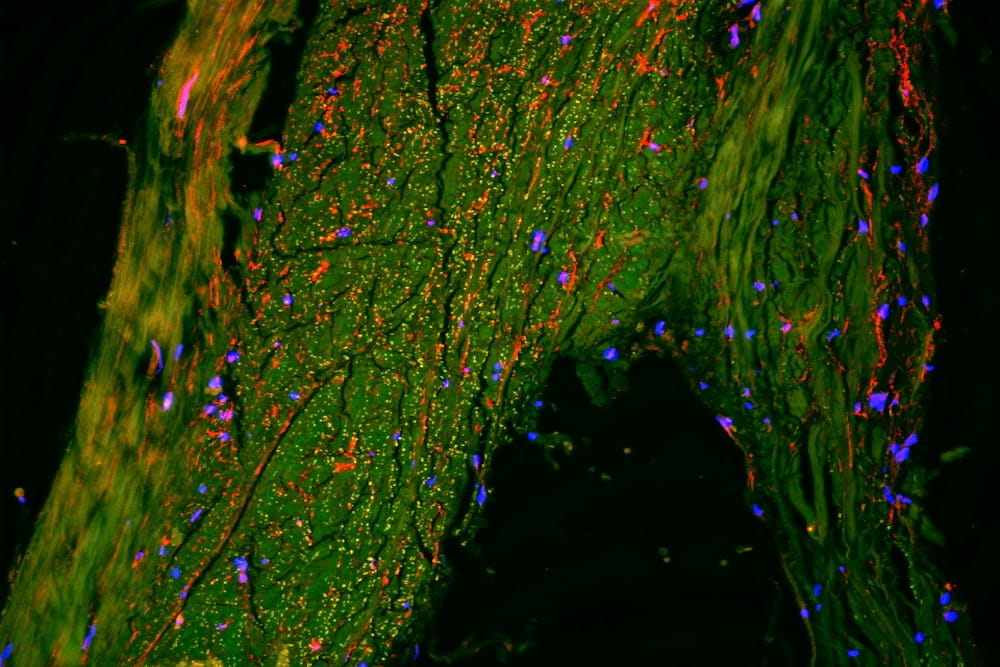

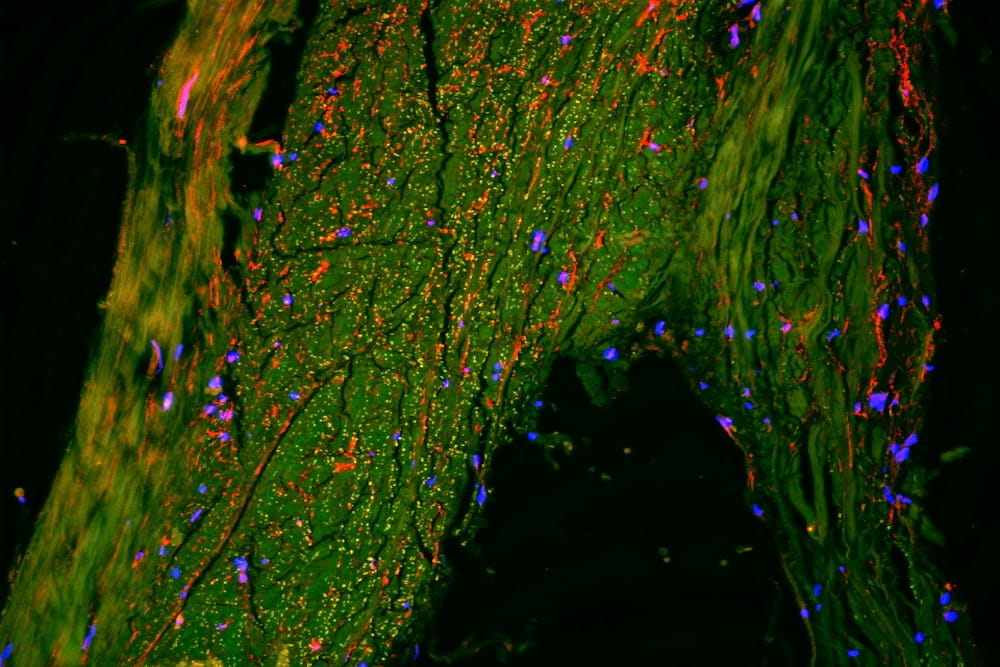

The recent grant, Translation of a Biomarker Panel for the Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, builds on previous research that investigated the change in the sugars secreted by liver cancer that contain altered sugar. Experts in this area, Mehta and colleagues examine the sugar-containing proteins that change in cancer and pass them along to proteomics experts to determine what those proteins are, a process called glycoproteomics.

“We did that back in 2003, 2004. We identified maybe 40 or 50 proteins that changed significantly in liver cancer that could act as a biomarker for liver cancer, so that was good.”

The challenge was how to make this clinically and commercially available, so that’s what this recent grant helps accomplish, he said. As it stands now, people at risk for developing liver cancer would need to get tested every six months with an estimated cost of $1,000 per test.

“Let’s say I'm 40 years old, and I've got to go for the next 40 years and pay $2,000 a year just to be told I don't have liver cancer? That's a lot of money,” he said. “It dissuades people from going, and when you dissuade people from going, the tumor can get to a point of no return.”

The latest grant will help commercialize an assay that can be accessed in a wide variety of places, hopefully at a cost of under $100.

Mehta and colleagues founded a company called Glycotest that will commercialize the blood test to serve as a potential biomarker. They are licensing an agreement to offer the test in China. Interestingly, while there are about 40,000 cases of liver cancer annually in the U.S., that number in China is over 400,000 cases.

“We've ported that test to a Chinese company as well, and, hopefully, they're going to offer that in China at an affordable price for that population. I expect it to be available in China by the end of the year. In the U.S., we're doing multiple sites, so it will take a bit longer, but we'll get there. Hopefully, it will be available by the end of 2019 in China and the end of 2020 or the beginning of 2021 in the U.S.”

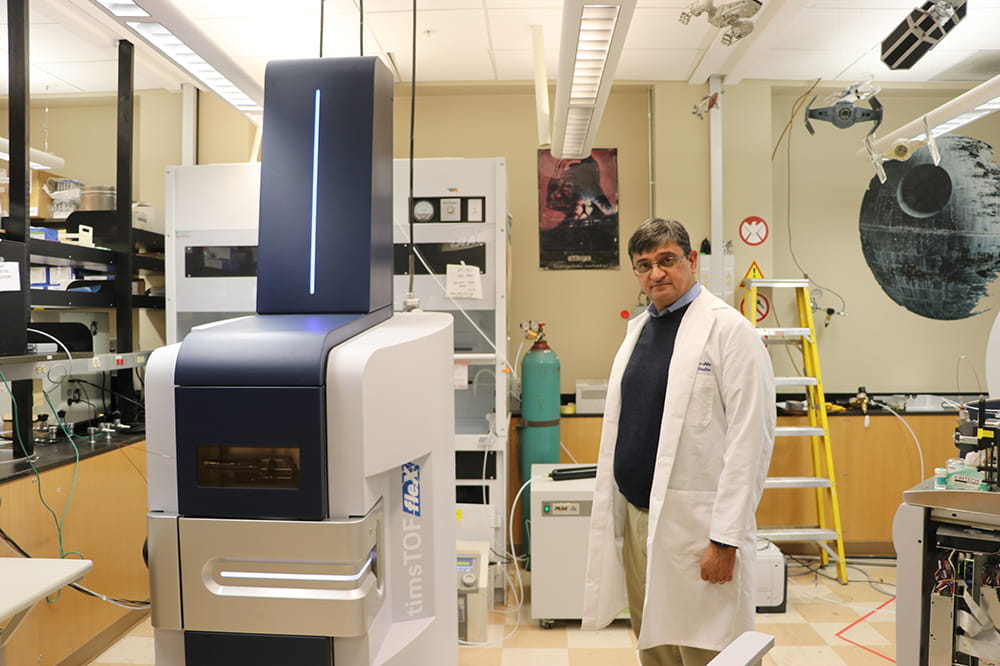

Mehta says this research is part of a portfolio of studies that tie together in interesting ways. A $3 million NCI grant he received in March allows for the testing of tumors that have been removed using a high-end mass spectrometer to determine how aggressive the cancer is to guide treatment protocol more effectively.

Mehta has partnered with Hollings Cancer Center researcher Richard Drake, Ph.D., the Smartstate Endowed Chair in Proteomics, to make that process more efficient by using a less expensive clinical-grade machine available in any clinical lab, rather than the very high-end mass spectrometer. They, along with other scientists from MUSC’s Department of Pharmacology, recently formed a company called Glycopath to commercialize the tissue analysis and the eventual analysis of signatures that may be predicative of drug responses, Mehta said.

“We would like to do that in South Carolina. We would like to start doing that with clinicians at MUSC, hopefully to treat people at MUSC first.”

Another interesting area of exploration, funded by an $844,971 NCI grant awarded in August, investigates the development of a rapid and efficient test to see if a patient will respond to a checkpoint inhibitor based upon a cancer tumor’s glycan profiling. There's a new class of chemotherapeutic agents called checkpoint inhibitors, and researchers have found that the glycans on the tumor cell can affect the T-cells, important in immune response, to keep them from functioning properly.

However, doing that glycan analysis is difficult and time-consuming, he said. “So, the grant that we just got will allow us to do that analysis on both the tumor cell and the T-cell in literally a few hours, using just a single slide,” Mehta said.

Mehta said the three grants are designed around developing tests and methods that hopefully will identify people with hepatocellular carcinoma, know more about their tumor type and provide more appropriate treatment.

With so many research projects in progress, it may seem like a challenge to balance everything. But Mehta doesn’t see it that way at all.

“We have a lot of balls in the air. But we have good people, and we have a great team,” he said. “And, we have good students who really have bought into what we're doing – into both the commercial and clinical importance about what we're doing. I think that is key, having good people and a supportive environment. I think that's really what you need.”

Mehta said it’s all about collaboration and incremental improvements.

“Even if we published a paper and someone then took that research and developed something fantastic with that? That’s wonderful –that's a success. It's a group effort, and we're all involved in this,” he said. “I want to improve the lives of people with liver cancer, and any way I can do that, I'll do it.”

MUSC scientists have discovered, for the first time in people, a previously unknown pathway that helps the brain to drain away waste.

Noted liver cancer researcher joins Hollings Cancer Center